Konark: Even beyond the Kama Sutra

Droves of tourists go to Konark because the 13th century Sun Temple there, built in the shape of a massive and elaborately carved chariot for the Sun God, is best known for its sculpted erotica.

Apparently, at the time the temple was built, wars and famines had caused the population to dwindle, and the rulers wanted people to go forth and multiply.

Therefore, the not-so-subtle hints: sculptures of fairly athletic sex, hot off the Kama Sutra press. A powerfully hedonistic Hindu message, in the midst of a wave of more austere Buddhist teachings. But there’s so much else in Konark, that to reduce it merely to erotica is unfair.

Here, for instance, are the spokes of the Sun God’s chariot wheels. Kon (angle) + arka (the sun) = Konark. So, of course, the wheels also double as sundials.Yes, there’s two people having at it energetically in the first of the two featured segments, and more power to them. But look at the fabulous detail of the carving around them.

And here, below, is one of the spoke segments magnified. Now, doesn’t she look happy? Women relishing moments of contentment are rare enough as motifs in ancient sculpture, but even that – gladdening as it is – isn’t the point. It seems significant that she’s on the spokes of the Sun God’s chariot wheels – powerful emblems of the passage of time – telling us, perhaps, that there’s a time and place for everything in life. Konark’s really about vitality of every sort, every last bit of happiness to be drawn out of life, be it from sex, or from music, or sport, or food.

There’s Suryadev, the Sun God, musing rather loftily in one of his three perches:

But here also is a bunch of women singing and playing their instruments in gay and quite earthly abandon; no this isn’t a temple for people who think that religion isn’t, first of all, about life and living.

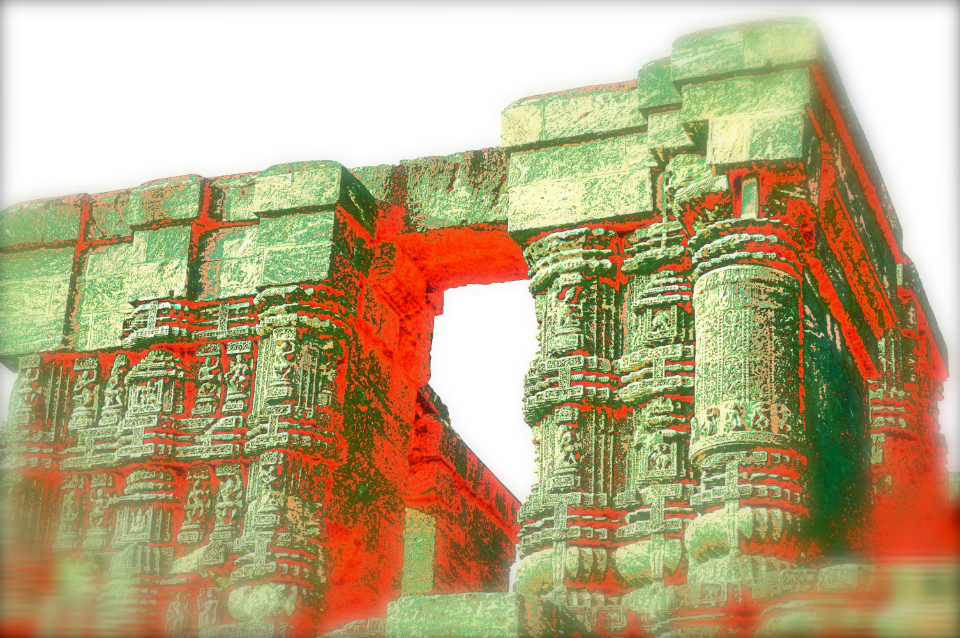

Here’s my very own makeover of the Nat Mandir, a section built especially for the music, dancing and plays. No wonder there’s a dance festival held at Konark every year. While the Nat Mandir’s too small to accommodate anything the size of a touristy modern festival, the temple must make a brilliant backdrop for nights of grand Odissi and Bharat Natyam recitals.

And here’s what I call my architectural take on those famous chariot wheels, a lateral view of one of the quite magnificent axles:

At a comfortable driving distance from Konark is Puri, of course, the old beach holiday favourite with people in Eastern India. Returning after several years, I found Puri crowded and not particularly attractive any longer. Much nicer beaches to be had at Gopalpur and other lesser known locations thereabouts. You’d best find rooms in Gopalpur or Puri if you want fancy accommodation; there’s only the one pretty basic government tourist lodge in Konark, but that’s the place to spend the night for the Konark sunrise.

The road from Puri to Dhauli, our next halt, has houses with these quite amazing doors. Small and otherwise modest homes, with doors that any urban art or interior director would give an arm for. Here is just one, and there’d have been a dozen more if our cab driver hadn’t been restive about stops.

More than Puri, the really interesting places from a historical point of view are Dhauli and the Udaygiri-Khandagiri Cave Complex. Here’s the Japanese Buddhist Peace Stupa at Dhauli; only half a century old, of course, but it marks the spot of a crucial event in Indian and Buddhist history.

And this is the great plain of Kalinga, shot from Dhaulagiri, the hill of Dhauli. Here, Emperor Ashoka saw the Daya river running blood after the Kalinga War, and renounced violence for good. Oh yes, of course, it could all have been strategic. But the fact is that Buddhism was just another tiny knot of protestants sedately picketing Brahminism until Ashoka propelled those ideas onto the world stage. And so this plain and the peace stupa that overlooks it mean a lot to those who believe that much of what the Buddha recommended makes sense even today, particularly today.

Ashoka left one of his inscribed edicts below the hill where the stupa now stands. The elephant head marks the top of the monolithic stone on which the edict is carved . The actual inscription is enclosed against vandals. We read the ASI translation and approved greatly of the rule that requires courtesy to those who serve you. The stupa can be seen at top left, and to its right is the Dhavaleshwar Shiva temple.

And below, are the rock-cut caves at Udaygiri. Here, and in neighbouring Khandagiri, Jain monks lived their stark and reclusive lives back in the 1st century.

Finally, historians derive much of what we know about that period from the famous Hathigumpha Inscription of King Kharavela, found in the Udaygiri caves. These inscriptions speak to us of the human need to record experiences, to make a mark on time. Perhaps, the same instinct as the one that makes me write this piece?

OMG-inducing, share-compelling, like-attracting, clutter-breaking, thought-provoking, myth-busting content from the country’s leading content curators. read on...