On A Mission to Keep Alive Oral Tradition of Languages

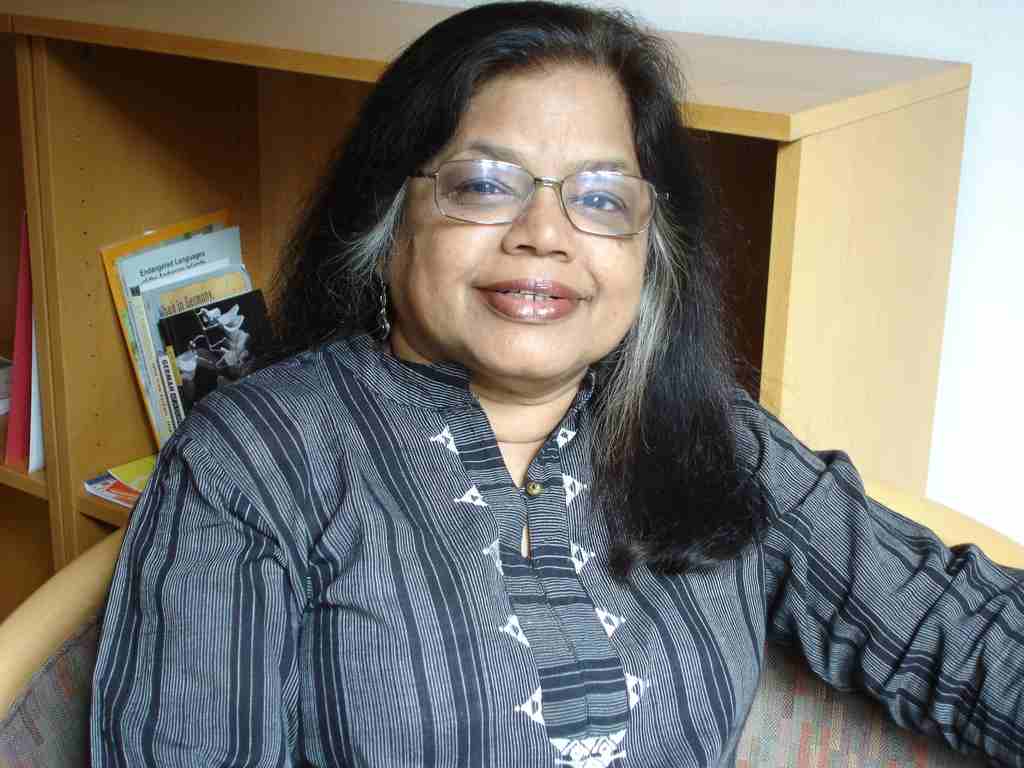

Anvita Abbi is on a mission to preserve the endangered languages of the country. A former linguistics professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru University and the present Director of Centre for Oral and Tribal Literature at the Central Sahitya Akademi, she believes these languages are the key to the intangible heritage for several tribal communities in India.

Abbi, who was recently in Odisha to participate in a language workshop, is currently working on creating a House of Voice in the Central Sahitya Akademi at New Delhi where she would preserve the sounds of unwritten forms of various endangered languages. “So far, no work has been taken up to preserve and archive the oral tradition in orality. While, Sahitya Akademi has several books on the oral tradition of languages, there are songs from endangered communities at Sangeet Natak Akademi. When it comes to oral narrations, there is no archive even as these languages have survived for over 100 years. This is a massive project and I do not know if I would be able to complete it, but someone has to make a beginning,” says Abbi, who received the Padmashree in 2013 and Linguistic Society of America’s Kenneth L. Hale Award in 2013 for her work towards preserving languages.

The idea for the House of Voice came from a meeting on languages by UNESCO that she attended in Barcelona in 2003. “There the organisers had come up with a Hall of Voice where they had archived the oral tradition of over 1000 languages from all regions of the world. So I thought of emulating the project here because India has a much older tradition of oral languages than any other Western country,” says Abbi.

She informs that there are 156 endangered languages in India and each of them are spoken by a population of less than 10,000. Even the Census of India does not publish their details. While, she has already worked on many of these 156 languages, Abbi is now focusing on preserving the tribal languages of Toda in Nilgiris and Halbi in Jagdalpur, Chhattisgarh, as a part of the project. She is the only linguistic in the country to develop a script for the Greater Andamanese languages, which were dying out due to Hindi.

She feels the Odisha Government should also start scripting the tribal languages spoken in the State. “Odisha is home to 62 tribal communities and it is interesting to note that each of them have a different language, which have survived till today because of their oral tradition. Scripting is the only way of archiving and conserving these languages and this is the most important aspect that the Odisha Government has to look into,” says Abbi, who was also the Advisor to UNESCO on language issues.

She adds that oral tradition of languages might have survived all these years but with the advent of globalisation, it faces the fear of extinction. “In fact, English and Hindi have been the silent killers of State and tribal languages. Where ever English has reached, it has killed the local language gradually, be it China, Sri Lanka, Africa, Singapore and now India. To make things worse, we Indians do not promote mother tongue-based education. Mushrooming of English schools and the fascination of Indian parents towards English education is the best example,” she says. Studies have shown that a child’s brain develops the best if he is educated in his mother tongue in the first three years of schooling, she says, adding that the Government should intervene to make mother-tongue based learning mandatory for students, primarily for those belonging to the tribal communities.

She further says that there is a large dropout rate in schools in rural parts of the country because students do not understand Hindi. “During my work at Chhattisgarh, I had come across a school where students were made to run under scorching sun by the teacher for not being able to answer some questions. When I asked them in Chhattisgarhi as to why did not answer the questions, the girls replied that the teacher spoke in Hindi, which they did not understand. In a way, we are depriving these students of the right to learn by forcing Hindi and English upon them,”she says, adding that Indian Vedic literature has survived since ages because of its orality. “We all know that they were written down much later,” she smiles.

Also Read:

OMG-inducing, share-compelling, like-attracting, clutter-breaking, thought-provoking, myth-busting content from the country’s leading content curators. read on...